Five years ago today, on May 1st, 2005 OASIS approved Open Document Format 1.0 as an OASIS Standard. I’d like to take a few brief minutes to reflect on this milestone, but only a few. We’re busy at work in OASIS making final edits to ODF 1.2. We’re in our final weeks of that revision and it is “all hands on deck” to help address the remaining issues so we can send it out for final public review. But I hope I can be excused for a short diversion to mark this anniversary.

I won’t talk much about the 5 years since ODF 1.0 was approved. The ODF Alliance and their “ODF Turns Five” [pdf] does a good job there. But I would like to talk a little about ODF and why it is so important that it came about when it did, why it was so timely.

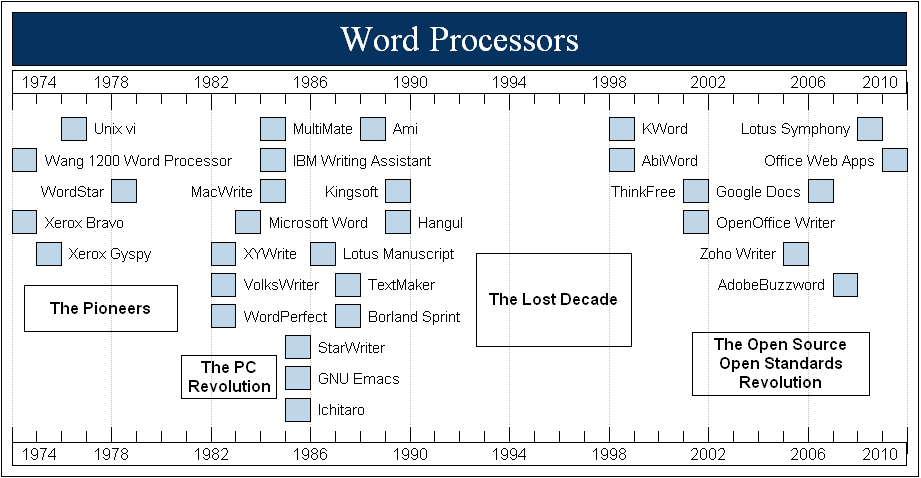

To fully appreciate the significance of ODF you need to understand the market climate in which it was created, and to understand that you need to understand a little of the history of word processors. The following time line illustrates the introduction dates of word processor applications over the past 30 years or so. You will notice some familiar and not-so-familiar names:

We can divide this time line into four time periods, each one driven by a pivotal development.

The first period was the “Pioneering Age”, when the first steps toward the modern word processor were taken. This was research-driven, primarily by Xerox PARC, who developed the first WYSIWYG word processor, Bravo as well as the first GUI word processor, Gypsy. Except for the line editor vi, which still has some adherents among the troglodyte cave dwellers, none of these first-generation applications survived, though their influence did. For example, Charles Simonyi, after working on Bravo at Xerox, went to Microsoft to develop Word. (Ah, the days before software patents…)

The next wave of word processor applications, the “Personal Computer Age” came in the 1980s with the new platforms of the IBM PC (1981) and the Apple Macintosh (1984). New platforms require apps, either new or ported, and you will see several familiar names introduced in that fruitful period.

Then we have a gap. From around 1990 to 1999 we do not see many new word processor introductions. This was the “Lost Decade”. New word processor introductions died off. Unchallenged by competition, even Microsoft Word advanced relatively little in this decade, compared to innovations before or since.

A few forces were at play here. First, there was a platform shift, from MS-DOS to MS-Windows 3.1 (1991) and Windows 95 (1995). Few companies were able to successfully port their applications to Windows. Also, the market changed significantly with the introduction of Microsoft Office as a suite of applications. Suddenly it was not enough to have a good word processor, say WordPerfect, or a good spreadsheet, say 1-2-3, or a good presentation package, say Harvard Graphics. To be competitive you needed to have all three suite components. And few companies did. Finally, there was the preferential access to operating system technical information Microsoft gave to their own applications teams, allowing Microsoft apps to run better on Microsoft operating systems than their competitors could. The decade closed with word processor competition wiped out. Analysts stopped tracking and reporting market share data when Office’s share exceeded 95%. And file formats? There were the binary DOC, XLS and PPT. And the file format documentation was only available under license from Microsoft, and only if you agreed not to make a competing word processor.

That was the shape of the market around 2000. Or more properly the state of the Microsoft monopoly.

So what happened that made ODF possible? In one word, the Internet. Well, not so much the technology of the internet itself, but widespread access to the internet via the web. This enabled the open source movement as we know it today to scale. Although open source existed before the web, unless you were at a major university or research centers, sharing source code and working collaboratively on software was very difficult. But with widespread access to email, ftp, web, eventually version control, we had the tools needed to scale open source from small teams to large teams. And to write a competitor to Microsoft Word you need a substantial team.

Why was open source so important? Because no rational profit-seeking entity would compete against a monopoly, especially one maintained by restricting access to technical information needed to interoperate. Lacking effective government regulation, the market was revived by open source. You see the same thing happen with Linux and with web browsers.

The other thing the internet and the web brought was a new platform based on open standards, HTML, CSS, XML, Javascript, allowing an interactive style of web application called “AJAX”. And since this new platform was based on open standards, Microsoft was less effective in preventing competition in this area. Certainly they tried. From ActiveX to Silverlight, from poor standards support in Internet Explorer, to the infamous memo by Bill Gates in 1998: “One thing we have got to change in our strategy – allowing Office documents to be rendered very well by other peoples browsers is one of the most destructive things we could do to the company. We have to stop putting any effort into this and make sure that Office documents very well depends on PROPRIETARY IE capabilities”, they tried, but ultimately failed to “take back the web” and turn it into a proprietary Microsoft platform.

With the new web application platform came new web-based word processors, some of which are charted above.

The net effect is that since 2000 or so we have a new diversity of word processors, open source, web-based, even the revival of commercial competition. It was against this backdrop, the history of competition and diversity all but wiped out but then restored in the new millennium, that ODF was born. Today every word processor of note supports ODF, including Microsoft Word. As Microsoft’s National Technology Director, and former CIO of Washington State, Stuart McKee said, “ODF has clearly won“. We’ve scaled the steep walls of monopoly and planted a new flag. Our former opponents are now our colleagues, working with us on ODF 1.2. We’ve shown we can win. But now we need to show that we can rule. This is the challenge. We need to continue to evolve ODF to meet user needs — and these are diverse needs — as well as accommodate a wide range of application models, from traditional heavy-weight desktop applications, to mobile apps, to web based apps, while realizing that these platforms themselves are shifting and possibly converging. Standards advance at glacial speed, while technological and competitive forces move at faster speeds. Allowing flexibility and extensibility while at the same time preserving interoperability among ODF implementations — this is a hard task, and one that is not entirely technological. The key value of ODF is to support interoperability in a market of diverse applications. This is the choice that users want.

But enough of the reflection. Time to get back to my work on ODF 1.2. I need to figure out linear depreciation according to the French accounting system so we can specify the AMORDEGRC spreadsheet function properly.