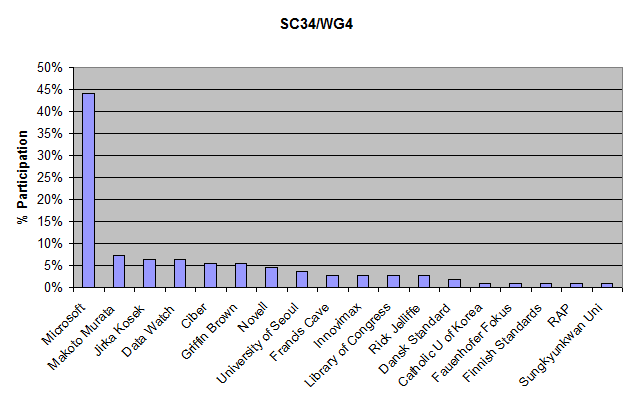

This is Part III of an 5-part series on the state of OOXML today. Previous to starting this series, I had not posted about OOXML in over a year. Part I showed how Microsoft, despite their promises that control of OOXML would be handed over to an independent, international committee, have instead stuffed the committee that maintains OOXML (JTC1/SC34/WG4) with Microsoft employees. And in Part II I looked at how the final published text of OOXML failed to account for all BRM decisions, and described the steps that ISO was taking to remedy this obvious procedural flaw.

In this Part I’ll look at how Microsoft is using their dominance in SC34 to push through hundreds of changes and additions to OOXML, in a misuse of a procedure intended for correcting drafting errors, to make OOXML “conform” to Microsoft’s monopoly product.

Let’s start by taking a look at the OOXML defect log [PDF] that SC34/WG4 uses to track their large list of errors and omissions discovered in the published standard. This defect report currently amounts to over 800 pages, longer than the entire ODF 1.0 standard. But it is well worth downloading and browsing through.

Some of these changes will be made in Technical Corrigenda while others are proposed for Amendments. What is the difference? SC34/WG4 itself made the distinction clear, in a presentation (N 1187 for those with access) it made to the SC34 Plenary in Prague, where it outlined its practice for deciding which changes would be made in corrigenda versus amendments:

All of the following criteria should be met for the defect to be resolved by Corrigendum:

1) WG 4 agrees that the defect is an unintentional drafting error.

2) WG 4 agrees that the defect can be resolved without the theoretical possibility of breaking existing conformant implementations of the standard.

3) WG 4 agrees that the defect can be resolved without introducing any significant new feature.Unless all the above criteria are met, the defect should be resolved by Amendment.

These are reasonable criteria and no objections were made when these guidelines were presented to SC34.

A key procedural point is that in ISO/IEC it is the JTC1 NBs who are the consensus body that has the authority to create international standards. All ballots which create or substantial modify standards must be approved by JTC1. This includes DIS ballots, FDIS ballots, FDAM ballots and DTR ballots. So standards, technical reports and amendments are ultimately approved or disapproved by JTC1 NBs. Although subcommittees in JTC1, such as SC34, provide the technical expertise and author and review work, they are not the standardizing authority. The exception that proves the rule is with corrigenda, which are authored and approved entirely at the SC level. However, this small area of autonomy in defect correction comes with carefully delineated bounds. A SC can author, approve and publish corrigenda by itself, but only to make corrections.

So if we look at JTC1 Directives 15.4.2.2, we read (with my emphasis) “A technical corrigendum is issued to correct a technical defect…. Technical corrigenda are not issued for technical additions which shall follow the amendment procedure…”. And in 15.4.1 “technical addition” is defined as: “Alteration or addition to previously agreed technical provisions in an existing IS.”

So amendments, which require approval by JTC1, are used for altering or extending the provisions of a standard, while corrigenda are used to correct errors introduced in drafting or publication. This dichotomy is common in other standards organizations. For example, in OASIS, a technical committee is able to approved and publish “Approved Errata” but these are restricted to changes that do not break conformance of existing implementations. Anything beyond that is considered a substantive change to the standard and requires review approval by the OASIS membership.

Clear enough? In fact, in many cases WG4 appears to follow this important distinction. Some of the proposed changes are simple and benign. For example, some BRM issues were fixed, but in being fixed caused informative example markup in the standard to be incorrect. A quick fix of these items via corrigenda is most welcome.

However, in other cases (in fact most of the cases), the Microsoft-dominated WG4 appears to have overstepped the permissible bounds for corrigenda, and indeed gone far, far beyond what it stated it would be doing in corrigenda. Let’s look at a few examples.

(Sadly, the general public is not given access to the text of the draft corrigenda (the DCOR) but those on the inside can follow along by reading N 1252 in the SC34 document repository.)

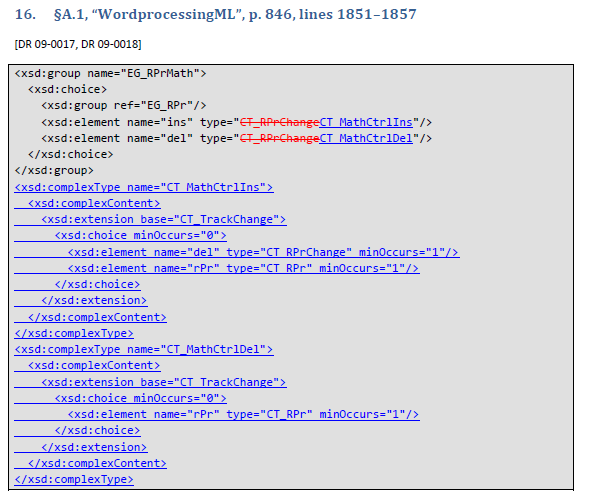

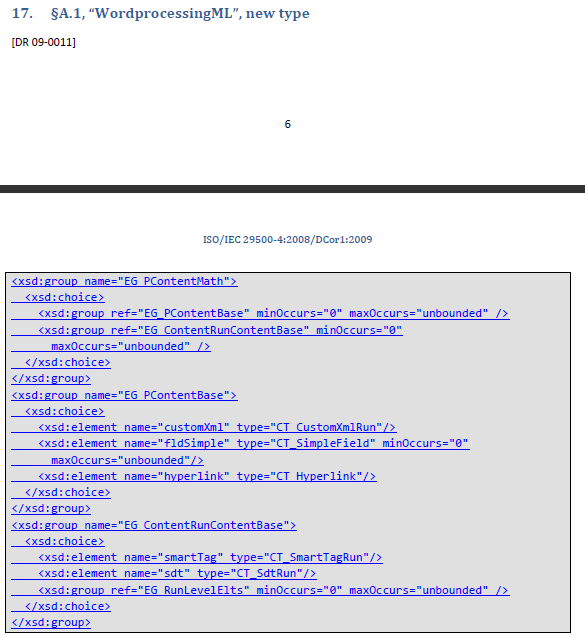

Let’s start by looking at items 16, 17, 36, 52, 53 and 133 in DCOR for ISO/IEC 29500 Part 4. These make changes and additions to the WordProcessingML schema. Deletions are noted in red strikethroughs, and additions in blue:

This is not correcting a drafting error. This is not correcting a publishing error. This is a substantial addition to the schema as you can see above.

It is argued, in the defect log, that this change is needed because, without it, ISO/IEC 29500 cannot represent change tracking in mathematical equations. However, this is exactly the type of change that WG4’s guidelines and JTC1 Directives exclude from corrigenda and place into amendments. The schema of OOXML is certainly an “agreed technical provision of an existing IS”. So how can adding math change tracking support to the schema be anything other than an “addition to previously agreed technical provisions”? And how can anyone in WG4 believe that adding dozens of lines to the schema can be done “without the theoretical possibility of breaking existing conformant implementations of the standard”? What about, for example, applications that were programmed to use the published OOXML schema, such as any application that uses a validating parser, or an schema-directed editor, or a program that generates code stubs from the schema, or does XML-to-relational DB mapping? Not only is there a theoretical possibility of breaking such applications, there is a theoretical certainty.

(Ironically, it should be noted that Microsoft was very keen to beat up on ODF for not having change tracking for mathematical equations, all while hiding the fact that OOXML lacked complete support for this feature as well.)

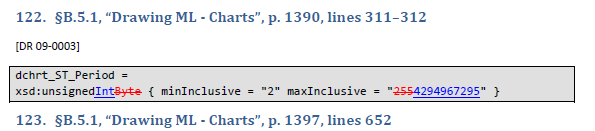

Another example, #122 in the DCOR.

It changes a type in chart, from a byte to an int and in doing so extends its allowed range considerably. How did anyone think that this was a change that was “without the theoretical possibility of breaking existing conformant implementations of the standard”? Isn’t there enough theoretical and practical expertise in WG4 to know that changes like this break compatibility?

For this change the rationale in the defect log explains the logic of it:

The standard states that the ST_Period simple type uses the XML Schema ST_Period data type and supports a range 2–255.

These observations are incompatible with existing documents and should be updated to reflect such prior art.

And so on and so on. If you search through the defect log, you will see the phrase “existing documents” used dozens of times. That appears to be how many discussions in WG4 end. It shuts down debate like an appeal to “national security” or “executive privilege”, arguments that trumps all others. It doesn’t matter what WG4 previously told SC34, or what JTC1 Directives say, if ISO/IEC 29500 does not match what Microsoft Office actually writes out, then this is by definition a drafting error, and the standard will be “corrected” to conform with MS Office. Let that sink in for a little, until you realize how backwards this is.

I invite you to go back to the defect log [PDF] and search for “BRM”. You will find several oddities. For example, among these proposed changes are some that actually reverse BRM decisions. Yes, you heard me correctly. SC34/WG4, the Microsoft-dominated committee that maintains OOXML, is undoing various BRM decisions that enabled OOXML to be approved in the first place. Why? Well, of course, to make the standard conform more to Microsoft Office.

For example, take DR 09-0159 “General: Unintended incompatibilities between Transitional schema and Ecma-376” or DR 09-0275 “BRM: serial date representation” with this comment:

Although this text is in accord with the detailed amendments resolved at the BRM, it is against the spirit of the desired changes for many countries. We believe that due to time limitations at the BRM, this change was made without sufficient examination of the consequences, and was made in error by the BRM (in which error the UK played a part).

(Norbert Bollow, a member of the Swiss NB, has some good analysis of the return of the leap year bug in spreadsheets. And Jomar Silva with the Brazilian NB tracks some additional breaking changes on a wiki.)

Ah, So WG4 is now interpreting the “spirit of the BRM” through their shamanic communion with the ISO Weltgeist, and each time their oracle come back with the same response: “Change OOXML so it ‘conforms’ to Microsoft Office 2007”. How convenient for Microsoft.

For most standards, multiple vendors work together to improve interoperability and to increase their conformance with the standard. But with OOXML a single vendor stuffs the committee and works to make the standard better conform to Microsoft’s monopoly product.

So although Microsoft Office does not conform to ISO/IEC 29500 today, I have no doubt that within a few months it will fully conform. But not a single line of code will have changed in the Office product. Office 2007 will be retroactively made to conform to ISO/IEC 29500. What will happen is the standard will be modified to match that single vendor’s products, by misapplication of an ISO procedure intended for fixing minor drafting errors.

So why go through all this trouble? I believe this is all about getting the OOXML standard “corrected” so Microsoft can push for it to get it officially adopted around the world. The only reason they’ve held back so far is because MS Office does not actually implement ISO/IEC 29500 today. So it would have been counter productive for them to push for official adoption. However, once this oversight is remedied, by changing the standard to match their product, then watch out.

The side effect, perhaps unintended, is that the OOXML standard is thus clearly marked to be unstable and unsuitable for adoption or implementation. With 800 pages of defects and more being found, and a Microsoft-dominated committee that changes the standard with no objective technical justification, the exact contents of the OOXML standard is tentative, uncertain and temporary. Four corrigenda documents and two amendment documents are currently being balloted, including many breaking changes. More corrigenda and amendments are on the way. There is no provision for a version attribute or any other indicator to declare which of the multiple incompatible versions of the standard a document conforms to. What competitor would risk implementing the standard, knowing that Microsoft dominates WG4, which has shown it is willing to change the standard at Microsoft’s whim? The risk is simply too large. A competitor would simply be putting their head in the lion’s mouth.

And at the same time WG4 rushes to make OOXML conform to Office 2007, Microsoft is moving on with Office 2010, now in technical preview. Office 2010 will be extending OOXML in hundreds of places. Where is SC34 in this? Where is the new work proposal for OOXML 1.1? Where the are discussions? The drafts? None of this exists. If Microsoft wanted to, they could have submitted these changes to SC34 at the recent meeting in Seattle, but they preferred to reserve discussion of the Office 2010 changes for a private meeting in Redmond the day after the SC34 Plenary ended, a snub to SC34 and their fictional control of OOXML.

So Microsoft is now off extending OOXML, and this whole ISO escapade with OOXML seems for naught. (I hear also that Microsoft is also backing off the submission of their Extensible Page Specification (XPS) to ISO as well, saying that “an Ecma Standard is good enough”.) It appears that Microsoft got what they wanted from ISO and is moving on. Who said it would last more than a night? As my grandmother used to say, “Why buy the cow when you can get the milk for free?”

In any case, the future looks like something like this:

- ISO/IEC 29500:2008’s future is uncertain. If the whole i4i patent thing goes against Microsoft, the standard will probably need to be withdrawn.

- ISO/IEC 29500 with Corrigenda and Amendments will eventually line up with Office 2007 SP2 sometime in 2010/11.

- But before that happens, Office 2010 will ship with hundreds of extensions that are not described in ISO/IEC 29500 but are documented in proprietary “implementation notes” on Microsoft’s web site.

- “Office 15” will ship sometime around 2013. It will have further proprietary extensions to ISO/IEC 29500, also not standardized. Office 15 will still be supporting “transitional” OOXML, just like Office 2007 and Office 2010 did. “Transitional” OOXML is the variation that has all the deprecated crud, like VML and “DoItLikeWord95” in it.

- “Office 16” will ship sometime around 2016. It will finally support the “strict” schema of ISO/IEC 29500, but with 3 generations of proprietary extensions layered on top of it. And that assumes ISO/IEC 29500 actually still exists. In 2015 — 5 years after its last amendment — it will be up for “periodic review” in ISO and may be withdrawn if it appears to have been abandoned by Microsoft.

The pattern is clear: OOXML will be extended by Microsoft much faster than it will be standardized and corrected by ISO. This will make the ISO version of OOXML, currently not supported by Microsoft, even more irrelevant in the future.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=5fb7acbe-1d71-4083-b891-acc702b48d98)