In Part 1 of this series we looked at a model of product adoption and market share that had a special and valuable property: the parameters of the model could be derived from a single survey question, e.g.:

“What is your awareness with the hand cream called Whizzo-Soft?”

A. I have never heard of it.

B. I have heard of it but I have never tried it.

C. I have tried it once.

D. I use it sometimes.

E. I use it regularly.

Given N responses to that survey questions you can derive the factors in the model by simple math:

- Customer Awareness = 1 – A/N

- Customer Motivation = (C + D + E) / (N -A)

- Customer Satisfaction = (D + E)/(N – A – B)

- Market Share = Customer Awareness * Customer Motivation * Customer Satisfaction

So let’s take a look at how this can be used in practice, taking the leading open source office productivity editor, OpenOffice, and the lesser known LibreOffice fork, as examples.

As mentioned in Part 1, the execution of the survey is critical here. Without a proper, random survey of the market, the results will not be accurate. In particular a survey of your current users will not work, since one of your goals is to find out what proportion of users are not familiar with your product.

So in this case I used Google’s new Consumer Survey service which uses sampling and post-stratification weighting to match the target population, which in this case was the US internet population. In other words, the survey is weighted to reflect the population demographics, for age, sex, region of the country, urban versus rural, income, etc. I did this survey in a personal capacity for my own interest. The Standard Disclaimer applies.

They survey question (and responses were):

What is your familiarity with the software application called “OpenOffice”?

- I have never heard of it

- I am aware of it but have never used it

- I have tried it once

- I use it only sometimes

- I use it on a regular basis

With 1502 responses, the results were:

| I have never heard of it | 72.4% |

| I am aware of it but have never used it | 9.3% |

| I have tried it once | 5.7% |

| I use it only sometimes | 5.9% |

| I use it on a regular basis | 6.6% |

And then with some simple arithmetic we have:

| Customer Awareness | 27.6% |

| Customer Motivation | 65.9% |

| Customer Satisfaction | 68.7% |

| Market Share | 12.5% |

What does that mean? In plain English:

- Around 1/4 of US internet users have heard of the OpenOffice software application. That is the brand recognition.

- Of those who have heard of OpenOffice, around 2/3 of them were sufficiently motivated to try the software.

- And of those who tried OpenOffice 69% were sufficiently satisfied with the software that they continue to use it.

- Overall, 1/8 of the surveyed population uses OpenOffice sometimes or regularly.

The absolute numbers are tricky to interpret in isolation. More interesting is to look at the numbers over time. The same survey question, with the same methodology was also given last September. The results and the change are in the following table, with changes having statistical significance (90% confidence level) emphasized in bold.

| OpenOffice | September 2012 | April 2013 | Change |

| Customer Awareness | 24.3% | 27.6% | 14% growth |

| Customer Motivation | 63.0% | 65.9% | 5% growth |

| Customer Satisfaction | 70.6% | 68.7% | 3% decline |

| Market Share | 10.8% | 12.5% | 16% growth |

The Apache OpenOffice project should be gratified that their efforts have paid off, and awareness of the product is increasing, as well as market share. This goes contrary to some loudly expressed concerns that the OpenOffice brand would languish at Apache. Clearly this is not so. The brand is growing, as well as the market share.

Since these factors are multiplicative, an increase in any one of them, or any combination of them, will grow the market share. But it is probably easiest to grow the factor that is smallest today. So looking to the future, increasing the awareness of the existence of OpenOffice would give the “biggest bang for the buck”.

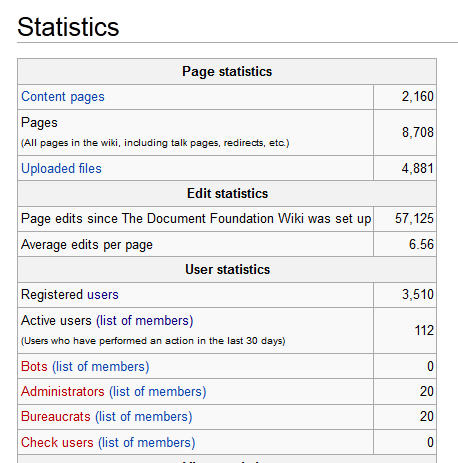

For an entirely different view we can look at the same survey question and methodology, administered at the same times, only substituting the product name “LibreOffice” for “OpenOffice”. Again, statistically significant changes are shown in bold.

| LibreOffice | September 2012 | April 2013 | Change |

| Customer Awareness | 10.7% | 9.9% | 7% decline |

| Customer Motivation | 53.3% | 66.7% | 27% growth |

| Customer Satisfaction | 73.7% | 59.7% | 19% decline |

| Market Share | 4.2% | 4.0% | 5% decline |

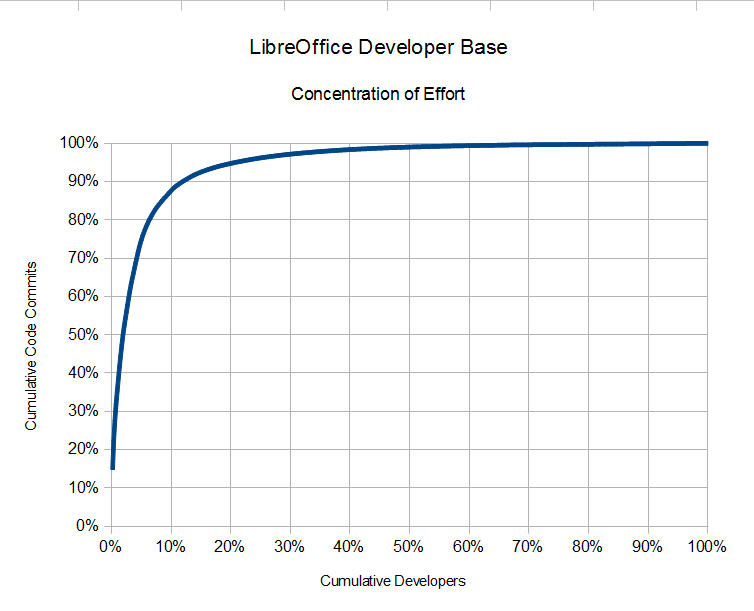

The brand recognition is not growing and is stuck at 10%. The fact that in its third year of product availability the LibreOffice brand recognition has plateaued (if not declined) should be a concern.

But the more interesting thing here is the large increase in users trying LibreOffice (Motivation) offset by the large decrease in users who continue to use the product (Satisfaction). What does this mean? Only the LibreOffice folks can say for certain, but this pattern is exactly what one would expect from a product where marketing has got ahead of quality. It is like a movie that previews well, but suffers from bad reviews and poor sales after the first weekend. Product development aims to make products that users want. And marketing persuades users to try the product. But where there is a disconnect between the two, where the product is not fulfilling the needs of those to whom it is being marketed, or (the same thing really) the product is being marketed to unsuitable users, this is what you see.

I should note that LibreOffice supporters like to blame their lack of success on not having the OpenOffice brand. Yes, having a familiar brand is a nice thing to have, but the drop in Satisfaction for those trying LibreOffice is not a brand issue, since it is entirely among those who are already familiar with the LibreOffice brand. Satisfaction is an attribute of the product, not due to brand.

Also, we can compare the metrics across products. When we look at the most recent data OpenOffice clearly has an enormous lead in name recognition and market share, but also a large lead in Satisfaction. 69% of those who tried OpenOffice remained users, compared to 60% for those who attempted to use LibreOffice. Keep your users satisfied and it is hard to go wrong.

Finally, and to reiterate up what I wrote earlier in my Scarcity Fallacy post, when you consider the position of Microsoft Office in this market, both products have a relatively small presence, with ample of room to grow, at Microsoft’s expense. This is a great area to advance the cause of open source software, in a product category that almost every user needs. There is no shortage of opportunity here, only a shortage of imagination. Imagine if we combined the stability/quality and brand recognition of Apache OpenOffice with the enthusiastic marketing team of LibreOffice? (Combine our 50 million downloads with their 50 million press releases) What if we combined the disciplined development approach of OpenOffice with LibreOffice ‘s talented developers? Imagine what we could do?

Let’s admit it. LibreOffice has plateaued. They have their Linux desktop users, all 3% of the market that runs Linux on the desktop. This market share was not earned. These are not users that they won over. These are users they got via the control their corporate sponsors have over Linux distributions. They flipped a bit and instantly had that market share. But their sponsors are Linux vendors that have little motivation to reach beyond that niche market. (They certainly have little success doing so). The opportunity for growth is not on the Linux desktop, unless the goal is to merely be a small fish in an even smaller pond. Of course, LibreOffice could continue, and languish indefinitely as a pet project of a handful of Linux developers. Or they could work with us at Apache, and satisfy the Linux users, but do so very much more as well. This would also be a cost savings for LibreOffice’s corporate sponsors, no small factor in a world of declining PC sales. The choice now, as it always has been, is theirs.