I am not an accountant. However, as a Graham and Dodd value investor over the years, I’ve picked up some of the fundamental principles. A key one is the Matching Principle, that revenues and expenses should be booked in a way that clarifies the underlying business performance, rather than based purely on the timing of cash transactions. In some cases this requires the use of special accounts, for things like depreciation, where the lifetime of a fixed asset (say factory machinery) extends beyond a single revenue cycle.

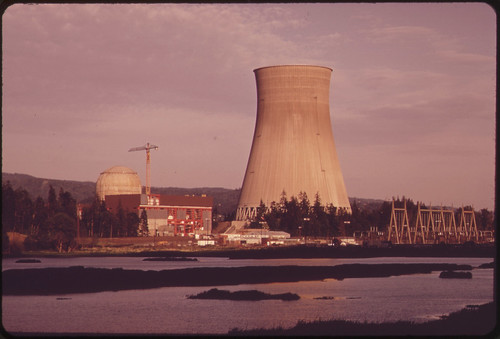

A similar technique is used when dealing with deferred expenses. For example take the case of a nuclear power plant. A plant has a useful lifetime, but when that end date arrives there is a clean up cost. The property is not immediately usable for other purposes, but must undergo an expensive remediation. From an accounting perspective there is an asset retirement obligation, a form of deferred expense. This deferred expense is recognized on the books as a liability based on the present value of the expected clean up cost, which is then depreciated.

I think of vendor lock-in in a similar way, but one where the clean up costs are commonly not recognized, either formally or even informally, as a deferred expense. Instead, the costs are attributed 100% to any alternative vendor. This leads to absurdities like the claim that moving to OpenOffice from Microsoft Office would be a huge expense. That is like saying that an old, non-functioning power plant cannot be used for any other purpose because the cleanup costs are too high. The costs could be real, but we only obscure the economic reality when we recognize vendor lock-in only at exit. It should have been considered at the entrance, and as a liability against picking a closed solution.

Something to consider. When you pick:

- A closed solution

- A non-open standard

In those cases you are risking vendor lock-in. And by doing so you are committing your company to either a perpetuity of lock-in, or to a future expensive remediation to restore your options to the point where you can make alternative choices. The smart way of doing this is to consider, in terms of analysis to aid decision making, the cost of lock-in up-front, as a deferred expense, a liability. When this is done you can more accurately make comparisons among available solutions, closed and open, knowing that you are fairly accounting for the true economic costs of each choice.