This is Part II of a four-part post.

In Part I we surveyed of a number of different problem domains, some that resulted in a single standard, some that resulted in multiple standards.

In this post, Part II, we’ll try to explain the forces that tend to unify or divide standards and hopefully make sense of what we saw in Part I.

In Part III we’ll look at the document formats in particular, how we got to the present point, and how and why historically there has always been but a single document format.

In Part IV, if needed, we’ll tie it all together and show why there should be, and will be, only a single open digital document format.

To make sense of the diversity of standardization behavior reviewed in Part I it is necessary to consider the range of benefits that standards bring. Although few standards bring all of these benefits, most will bring one or more.

Variety Reduction

Standards for screw sizes, wire gauges, paper sizes and shoe sizes are examples of “variety-reducing standards”. In order to encourage economies of scale and the resulting lower costs to producers and consumers, goods that may naturally have had a continuum of allowed properties are discretized into a smaller number of varieties that will be good-enough for most purposes.

For example, my feet may naturally fit best in size 9.3572 shoes. But I do not see that size on the shelves. I see only shoes in half-size increments. Certainly I could order custom-made shoes to fit my feet exactly, but this would be rather expensive. So, accepting that the manufacturing, distribution and retail aspects of the footwear industry cannot stock 1,000’s of different shoe sizes and still sell at a price that I can afford, I buy the most comfortable standard size, usually men’s size 9.5.

And yes, Virginia, there is also an ISO Standard for shoe sizes, called ISO 9407:1991 “Mondopoint”.

Decreased Information Asymmetry

A key premise of an efficient & free market is the existence of voluntary sellers and voluntary buyers motivated by self-interest in the presence of perfect information. But the real marketplace often does not work that way. In many cases there is an asymmetry of information which hurts the consumer, as well as the seller.

For example, when you buy a box of breakfast cereal at the supermarket, what do you know about it? You cannot open the box and sample it. You cannot remove a portion of the cereal, bring it to a lab and test it for the presence of nuts or measure the amount of fiber contained in it. The box is sealed and the contents invisible. All you can do is hold and shake the box.

The disadvantage to the consumer from this information asymmetry is obvious. But the manufacturer suffers as well. This stems from the difficulty of charging a premium for special-grade products if this higher grade cannot be verified by the consumer prior to purchase. How can you sell low-fat or high-fiber or all-natural or low-carb foods and charge more for those benefits, if anyone can slap that label on their box?

The government-mandated food ingredient and nutritional labels solves the problem. The supermarket is full of standards like this, from standardized grades of eggs, meat, produce, olive oil, wine, etc. There are voluntary standards as well, like organic food labeling standards, that fulfill a similar purpose.

Compatibility

Compatibility standards, also called interface standards, provide a common technical specification which can be shared by multiple producers to achieve interoperability. In some cases, these standards are mandated by the government. For example, if you want to ship a letter using First Class postage, you must adhere to certain size and shape restrictions on the letter. If you want to to send many letters at once, using the reduced bulk rate, then you must follow additional constraints on how the letters are addressed and sorted. If you want to deal with the Post Office, then these are the standards you must follow.

Similarly, if you are a software developer and you want to write an application that does electronic tax submissions, then you most follow the data definitions and protocols defined by the IRS.

Required interface standards are quite common when dealing with the government. Regulations requiring the use of specific standards also promote public safety, health and environmental protection.

And not just government. A sufficiently dominant company in an industry, a WalMart, an Amazon or an eBay, can often define and mandate the use of specific standards by their suppliers. If you want to do business with WalMart, then you must play by their rules.

Network Goods

Where it gets interesting is when compatibility standards combine with the network effect. I’m sure many of you are familiar with the network effect, but bear with me as I review.

The first person to have a telephone received little immediate value from it. All Mr. Bell could do was call Mr. Watson and tell him to come over. But the value of the telephone grew as each new subscriber was connected to the network, since there were now more people who could be contacted. Each new user brought value to all users, present and future. When the value of a technology increases when more people use it, then you have a network effect.

In a classic, maximally-connected network, like the telephone system, when you double the number of subscribers, you double the value to each user. This also causes the value of the entire network — the total value to all subscribers — to square. So double the number of participants in the network, and the value of the network goes up four-fold.

Of course, this only works up to a point. There are diminishing returns. When the last rural villager in Albania gets a telephone connection, I personally will not notice any incremental benefit. But when we’re talking about the initial growth period of the technology, then the above rule is roughly the behavior we see.

Other familiar network effect technologies include the Internet’s technical infrastructure (TCP/IP, DNS, etc.), eBay, Second Life, social networking sites such as Flickr, del.icio.us or Digg, etc.

If we delve deeper we can talk about two types of network effects: direct and indirect. The direct effect, as described above, is the increased value you receive in using the system as greater numbers of other people also use the system. The indirect effects are the supply-side effects, caused by things like increased choice in vendors, increased choice in after-market options and repairs, increased cost efficiencies and economies of scale by a market that can optimize production around a single standard.

So take the example of eBay. The direct network effect is clear. The more people that use it, the more buyers and sellers are present, and the more value there is to all of the buyers and sellers. The indirect network effect is the number of 3rd party tools for listing auctions, processing sales, watching for wanted items, sniping, etc., which are available because of the concentrated attention on this one online auction site.

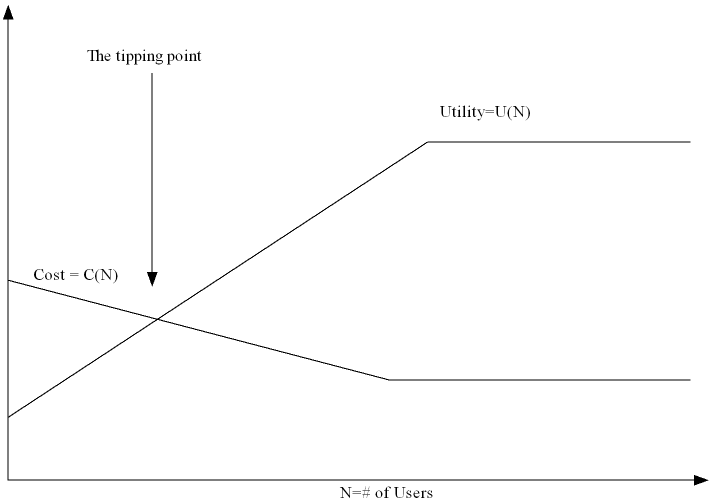

It might be helpful to look at this graphically. The following chart attempts to show two things:

- How the average per-user cost of using the technology C(N) decreases as more people join the network.

- How the average per-user utility (value) U(N) increases as more people join the network.

A few things to note:

First, utility does not increase without limit and cost does not decrease without limit. There will be diminishing returns to both. Remember that last villager in Albania.

Also, note that initially the average cost is more than the average utility. But this is only the average. Not everyone’s utility function is the same. If they were, then network would never get started. Fortunately, there is a diversity of utility functions. Some users will see more initial value than others, and they will be the early adopters. Some will see far less value than others and they will be the late adopters.

Finally note the point marked as the “tipping point”. This is where the largest growth occurs, when the average user’s utility is greater than the average users’ cost.

Network Effect Compatibility Standards

So what does this all have to do with standards? My observation is that a single standard in a domain naturally results when there are strong direct and indirect network effects. And where these network effects do not exist, or are weak, then multiple standards flourish.

This can be seen as societal value maximization. A network of N-participants has a total value proportionate to N-squared. Split this into two equally-sized incompatible networks and the value is 2*(N/2)^2 or (N^2)/2. The maximal value comes only with a single network governed by a single standard.

Allowing two different networks to interoperate may be technically possible via bridging, adapting or converting, but this at best preserves the direct network effects only. The indirect effects, the economies of scale, the choice of multiple vendors, the 3rd party after-market options, etc., these reach their maximum value with a single network. The indirect network benefits essentially follow from the industry concentrating their attention and effort around a single standard. When split into multiple networks, the industry instead concentrates their attention on adapters, bridges and convertors, which requires effort and expense on their part, with the cost eventually passed on to the consumer, although it brings the consumer no net benefit over having a single network.

The Cases from Part I

Let’s finish by reviewing the cases presented in Part I, in light of the above analysis, to see if those examples make more sense now.

- Railroad gauge — This is clearly a network compatibility standard, with strong direct and indirect effects. When everyone uses the same gauge, travelers and goods can travel to more places, faster and at less cost. The indirect effect is that it allows the train manufacturer to concentrate on producing a train that fits a single gauge. As this happens the train companies have a greater choice of whom they can buy from. Everyone wins.

- Standard Time — This is more subtle, but it is also a network effect standard. The more people who use Standard Time, the easier it was to communicate times unambiguously and without error to others who were also using Standard Time. There is also an aspect of variety-reduction to this, where having fewer local times to worry about simplified the train time tables which made it easier for passengers and shippers or interacted with the trains.

- The single language for civil aeronautics. This is variety-reduction, a mandated safety standard, as well as a networked compatibility standard, where the network consists of pilots and control towers.

- Beverage can diameters — This is a variety-reducing standard. There is no network effect. Ask yourself, when you buy a can of Coke, does it bring more value to others who have also bought a can of Coke? No, it doesn’t.

- TV signals — Clearly this is a network compatibility standard, with strong direct and indirect effects. The network is not just of the viewers of TV. It also includes the networks, the local affiliates, and the companies that manufacture the hardware and software, from antennas and transmitters, to camera, editing software, televisions and VCR’s.

- The complexity of the above network is one reason why the government has stepped in to mandate the switch to digital television. (The other reason is the money they will get from auctioning off the radio spectrum this conversion will free up) The free market is good at many things, but the complex conversion of an entire network of diverse and competing producers and consumers at many levels is not something it has the agility to accomplish.

- Fire hose couplings — This started as a compatibility standard, but only at a local level. Baltimore had its own standard for its own fire company. However, as the railroad made it practical to transport fire companies from more distant cities, a larger network developed. By using the national standard hose coupling, you not only can now receive mutual assistance from other fire companies (direct value) you also have a greater choice of whom you can buy fire hoses from (indirect value), and fire hose manufacturers now have a larger market they can sell into (indirect value) and the concentration on a single coupling design (variety-reduction) will lead to manufacturing efficiencies and economies of scale (indirect value), as well as concentrated innovation around that standard (indirect value).

- Safety razors — There is no network effect with razors and razor blades. The value I get from using Gillette does not vary depending on how many other people use Gillette. I would get the same shave if I were the only one using it, as if the entire world used it.

- Video game consoles — These generally have been free of direct network effects, though there are clearly some indirect ones, in terms of varieties of titles, after-market accessories, etc. The interesting thing to watch will be to see whether the latest generation of game systems, the ones that allow play over the Internet, will lead to direct network benefits. Will this lead to standards in this area?

- SLR lens mounts, DVD disc standards, coffee filters, vacuum cleaner bags, etc. — These are all similar, compatibility standards with no direct network effects.

Well, this is too long already, so I’ll stop here.

In Part III I’ll look at the history of document formats, and see what factors have influenced their standardization. Some questions to think about until then:

- Some technologies, like rail gauges, local time or fire hose couplings went many years without standardization. Then, in a brief surge of activity, they were standardized. Look at the trends or events that participated the need for standardization. Is there any unifying logic to why these changes occurred? Hint, there is something here more general than just the trains.

- In the cellular phone industry, Europe and Asia made an early decision to standardize on the GSM network, while the U.S. market fragmented between CDMA, GSM and, earlier, D-AMPS. What effects does this have on the American versus the European consumer, direct and indirect?

- Microsoft has repeatedly stated that they are dead-against government mandates of specific standards. But they are a member of the HighTech Digital TV Coalition, an organization which is heavily lobbying the government to mandate Digital TV standards. How do we reconcile these two positions? Are they only against mandatory standards in areas where they have a monopoly?

- How does any of this relate to office document formats?

In Part III, we’ll look at that last question in particular, including an illustrated review of the history of document formats.

3/23/07 — Corrections: Bell not Edison invented the telephone (Doh!). Also corrected calculation in value of two networks.

This is very interesting.

Discussing the benefits of true standards is a much better way to promote ODF than arguments about why the alternative won’t be adopted. The point you bring are pretty exhaustive and help clarify my own mind.

Will you have something to say on standard suites like TCP/IP and XML? Some standards will deliver their benefits only when they come in a suite of related but independently written specifications. I think TCP/IP, PSTN and also television signals for example.

It is not publicized that XML is actually such a suite of standards. Its promises will be fulfilled only if a reasonably complete implementation of the suite is available. Microsoft picks and choose the elements on the suite it wants and this tactics leads to “intraoperability” as opposed to interoperability as Bob Sutor puts it. But Microsoft still claim XML support and this is a bit deceptive.

It is like someone claiming to support TCP/IP without supporting the routing protocols like RIP, OSPF and BGP. End devices can connect to such network but routing devices are kept proprietary. This is a trap Cisco did *not* fall into. Cisco provides a proprietary routing protocol, but they also support the standard ones. Therefore users that want to be fully standard can be and those that like the proprietary solution can still interface with standard compliant networks.

I have a minor nitpick about the following statement: “The free market is good at many things, but the complex conversion of an entire network of diverse and competing producers and consumers at many levels is not something it has the agility to accomplish.”

In the example you give there is no positive business case for the TV stations because digital TV, especially HDTV, has higher production costs, higher bandwidth consumption, huge transition costs and brings no additional revenue. This is why the market does not move of its own volition.

Complex transitions did occur from market forces in the past, for example the transition from black and white to color TV, transition from over-the-air TV to cable TV and the transition from X.25 and serial lines to TCP/IP networking. Witness also the currently on-going transition from PSTN to VoIP.

If Microsoft is pressing for digital TV standards while fending off government intrusion elsewhere, it does not surprise me. It has become a pushmi-pullyu or hydra of sorts by virtue of its size: any organization with tens of thousands of employees is going to find it hard to speak with one voice.

Incidentally, I am not sure whether file formats are comparable to the examples you mention. With the exception of digital TV, these–time, fire hose couplings, razors–are all mature technologies.

The fact that office document formats, e.g. DOC, have not changed in many years does not mean that the technology is ripe. It could also stem from the innovation-quashing effects of a monopoly. New document standards could help weaken this monopoly and thus spur innovation–there is still TONS of room for innovation in electronic documents. Yet, at the same time, standards often stifle innovation!

Does anybody have ideas for how to resolve this contradiction?

Queen Elizabeth asks “Does anybody have ideas for how to resolve this contradiction?”

This is an easy one. You design your standard around an extensible foundation that can dynamically grow a suite of innovative specifications over time. With this model you don’t have a single monolithic standard that freezes everything in stone. You have a suite of standards that grow in capability over time. You even have the capability to drop obsolete/failed specifications and replace them with something better.

An example is TCP/IP. The IETF adds new RFCs every year. The IEEE does the same with the 802 series of standards at the physical/data link layers. There is no shortage of innovation in networking but there is no shortage of immature technologies either.

Another example is the world wide web. The W3C consortium has successfully extended the web protocols over the years with muliple successive specifications. There is no shortage of innovation in the web. The major inhibitor is Microsoft because they don’t implement in IE the standards they don’t feel like implementing. As a result, web operators don’t use new standards by fear of shutting their audience off their sites.

Both examples are comparable to the document formats. XML is clearly a suite developped according to this model and ODF is meant to fit in nicely. The innovation inhibitor is Microsoft. They implement only the portion of the XML suite they feel like implementing using their usual embrace and extend strategy.

That’s a good point. A standard does not mark the end of innovation. It simply marks a point of stability on which producers and consumers can agree, and let the market form value chains around that stability.

But there will still be winners and losers. Remember the ladies of Erie, Pennsylvania, tearing up the new standard gauge railroad tracks because the standardization of gauge at this junction would cause their husbands high paid jobs loading and unloading cargo between incompatible tracks to disappear.

Standardization increases competition, and will be opposed by those who are unable or unwilling to compete.

> For example, my feet may naturally fit best in size 9.3572 shoes. But I do not see that size on the shelves. I see only shoes in half-size increments. Certainly I could order custom-made shoes to fit my feet exactly, but this would be rather expensive.

Just for reference, my custom shoes cost $460 all told. About $60 was for the design sewn into the leather and there was perhaps $20 for the shipping charge. They were molded to casts of my feet, so they fit me exactly. I was told by another leatherworker that those prices were very, very good if not cheap and he confirmed that their quality is excellent. They were made by a husband & wife team who operate their own business doing this.

So yeah, shoes would be a LOT more expensive without standards (although I really like mine).

Not to mention the LAN standard battle with Ethernet, token ring and token bus. Ethernet customers are enjoying very low cost parts and higher speeds but token ring never achieved the same market size and token-ring customers paid the price in incompatible infrastructure (my employer still has shielded token-ring cabling)

To be honest, having two competing standards wouldn’t be that big of a problem, per se — even if they each had almost 50% of the market.

The real problem here is that MS’s OOXML format, as documented, isn’t really a standard. It’s part of a product, and the only full implementation is likely to be from Microsoft … In fact there are some questions about the legality of a full Non-MS implementation.

As I see it, the biggest problem with MS’s OOXML specification is that it’s incomplete, and — even if it were completely documented — a full implementation would be a complete pig. More than that, there’s no real promise that — even if it’s accepted accepted as an ISO standard, MS would even stay with(in) the specification as documented.

It’s reasonably obvious that ‘ISO ODF XML’ (and with it OpenOffice.org) isn’t the end of the road.

Say I’ve got a Playstation 3, which is really wizzy at doing 3D visualisations. And I’ve been doing some modelling/visualisation of how Malaria parasites manage to infect human cells; or whatever Bill and Melinda’s Foundation is up to.

And I want to include it in my document, and communicate it with the scientists I’m working with so we can discuss whether the model reflects real life; whether we’re on the way to developing a pharmaceutical to fix the problem.

I’ve got a Playstation. You’ve got a Lenovo. He’s got an XBox.

Really nice if we can all interoperate. Then we can make progress.

For another major standardisation effort,

check out the floating-point standard

ANSI/IEEE 754-1985, and especially the

comments of one of the main architects, Prof. William Kahan.

I like you series of articles, but I have to raise an exception on one term: indirect network effects. I am not sure I agree with the defintion of indirect network effects and the use of that name. Those effects occur in cases where there is no direct network effect. Your razor and blades example for instance. “increased choice in vendors, increased choice in after-market options and repairs, increased cost efficiencies and economies of scale by a market” have nothing to do with whether there is a direct network effect at all. What you label as indirect network effects are really direct functions of the size of markets regardless of whether there are network effects in those markets. Therefore, I don’t think they should be called network effects of any kind–they are coincidental to the network and its growth–not a consequence of it.

Daniel, That is a fair point. I admit that am not 100% happy with the term “indirect network effect” either. I was going to simply refer to it as “economies of scale”, but it is more than that, since economies of scale typically refer to the benefits that accrue directly the producer alone, but what we’re talking about here, greater choice in vendors, after-market options, service, support, etc., is more than that.

Any one have suggestions for what else to call that? There must be a word for this already. I hate to be novel if I can avoid it.

I am no expert on network effects but I have found this article that seems authoritative enough. The key paragraph seems to support the concept of indirect network effect as a benefit that grow with the size of the market:

— Begin quote

The literature has identified two types of network effects. Direct network effects have been defined as those generated through a direct physical effect of the number of purchasers on the value of a product (e.g. fax machines). Indirect network effects are “market mediated effects” such as cases where complementary goods (e.g. toner cartridges) are more readily available or lower in price as the number of users of a good (printers) increases. In early writing, however, this distinction was not carried into models of network effects. Once network effects were embodied in payoff functions, any distinction between direct and indirect effects was ignored in developing models and drawing conclusions. However, our 1994 paper demonstrates that the two types of effects will typically have different economic implications. It is now generally agreed (Katz and Shapiro, 1994) that the consequences of internalizing direct and indirect network effects are quite different. Indirect network effects generally are pecuniary in nature and therefore should not be internalized. Pecuniary externalities do not impose deadweight losses if left uninternalized, whereas they do impose (monopoly or monopsony) losses if internalized. An interesting aspect of the network externalities literature is that it seemed to ignore, and thus repeat, earlier mistakes regarding pecuniary externalities. (For the resolution of pecuniary externalities see Young (1913), Knight (1924), and Ellis and Fellner (1943).)

— end quote

What about “mass-market effects?”